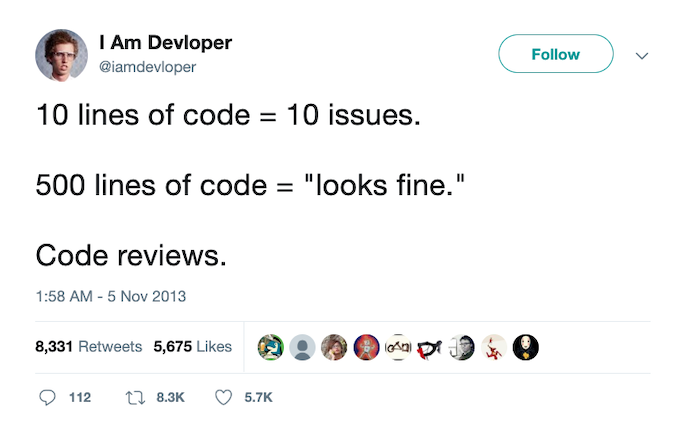

tl;dr: Keeping your pull requests small will lead to quicker and better quality reviews, allowing you to merge your glorious code into master much sooner.

Disclaimer: Many of the behaviours described in this post have been exhibited by myself. I am not directing criticisms towards anyone in particular.

Storytime

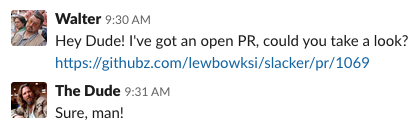

Picture this. You’ve just arrived at work. It’s a beautiful day, the sun is shining (not that you’ll be seeing any of it you hermit you 😉). You’re raring to code. You switch on your laptop and grab a cup of coffee. You reply to a few emails and see that you, yes you, have been hand-selected to review a pull request.

Positively flattered, you open it up only to be hit by a wall of red and green. You think, “what is this Lovecraftian-sized beast that stands before me?”. A changeset so big that you could develop RSI just by scrolling through it. Lucky for you, there are multiple requested reviewers. So you close the tab and forget about it.

20 minutes later…

You’ve been sucked right back in. There’s no escaping this now.

Headphones? Check. More coffee? Check. A copious number of biscuits? Check.

You open the PR again.

The summary stares back at you. Taunting you:

As you scroll through, you realise that despite what the description says, this PR doesn’t just add a new feature. There are refactorings, renamings, deleted files, reformattings, import reorderings, dependency upgrades, fixed typos, dead code removal and, finally, new code. And not just new code. A lot of new code. New code that could have been submitted independently in bite-sized chunks.

You spend the next 35 minutes going over the changes, trying to understand how all of this works whilst ducking and

weaving through superfluous updates. You gloss over certain parts (because life is too short). You leave a few

suggestions. There’s a bit of back and forth between you and the author. The code generally looks pretty good. And

with that, you bestow the honour of a pull request approval. You’re free at last. The monster is slain!

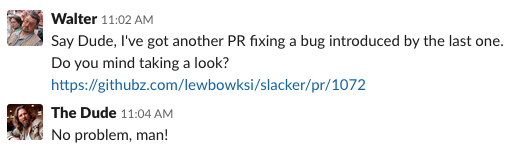

1 hour later…

You take a look at this new PR. You are overcome with joy and relief when you see:

It’s a fraction of the size of the previous PR. It’s to the point. It’s a bug fix and only a bug fix. Nothing more. Nothing less. You see what the problem originally was and how this PR fixes it. You understand it perfectly. You see how all the unit tests cover each edge case and will stop this bug from rearing its ugly head in the future. Reviewing this PR is a doddle and you submit your approval in no time.

But you’re left with an underlying feeling of disappointment. Disappointed that neither you nor the author spotted this bug in the original PR. It was glaringly obvious, albeit surrounded by a bazillion other changes. Maybe it was just a one-off.

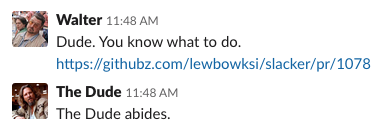

30 minutes later…

…of course, it wasn’t a one-off. There is rarely just one bug.

And so on and so on.

Now, this may be slightly exaggerated but I’m sure most of you have been in similar situations (having played both characters). I’m using this as a way to illustrate why I believe that keeping your PRs small will lead to faster and better quality reviews.

So what is a “Small PR”?

For me, pull requests should do one thing. Let me paraphrase the advice in Clean Code on functions:

Pull requests should do one thing. They should do it well. They should do it only.

Every line in your PR should contribute to that one thing. Anything that does not contribute to that one thing should be put on a separate PR.

Mixing bug fixes and new features? Put them on separate PRs.

Moving those classes that we aren’t using to a new package? Put them on a separate PR.

Those refactorings that have no relevance to this new feature? Put them on a separate PR.

Deleting old files that haven’t been needed for the past 3 years? Put it on a separate PR.

Writing two services that are completely independent of each other? Put them on separate PRs.

Choosing to do one thing in your PRs will naturally make them more focused and smaller (and reviewers will adore you for it!).

Why?

Faster reviews

Small PRs are easier to digest (assuming the author doesn’t write obscure one-liners). There’s no bouncing around files, scrolling for an eternity between a class and its test class. We don’t need to hold what seems like the entire codebase in our short-term memory. With the focus being on one thing, we reduce noise and distractions that can eat into precious reviewing time.

Have you ever delayed reviewing a huge PR because you found the task daunting? Of course, you have. We all have! Small PRs don’t just reduce the amount of time spent reviewing. They make it much more likely that a reviewer will begin their review ASAP.

Small PRs, mean less code, means less time trying to understand said code, means faster reviews.

Easier to spot problems

Time for a really basic example.

Give yourself a minute or so to read through the following code extract from a PR. Try to hunt down the fairly obvious error:

public void initialiseCells() {

for (int row = 0; row < grid.getRows(); row++) {

for (int column = 0; column < grid.getColumns(); column++) {

initialiseCell(new Coordinates(row, column));

}

}

}

private void initialiseCell(Coordinates coordinates) {

Cell cell = new Cell();

addAlivePropertyListener(cell);

addClickEventHandler(cell);

grid.add(cell, coordinates);

}

private void addAlivePropertyListener(Cell cell) {

cell.aliveProperty()

.addListener(newValue -> setAliveStyle(cell, newValue));

}

private void setAliveStyle(Cell cell, boolean isAlive) {

List<String> styleClass = cell.getStyleClass();

if (isAlive) {

styleClass.add(ALIVE_STYLE_CLASS);

} else {

styleClass.remove(ALIVE_STYLE_CLASS);

}

}

private void addClickEventHandler(Cell cell) {

cell.addEventHandler(MouseEvent.MOUSE_CLICKED,

event -> cell.toggleAlive());

}

public void resetCells() {

for (int row = 0; row < grid.getRows(); row++) {

for (int column = 0; column < grid.getRows(); column++) {

resetCell(new Coordinates(row, column));

}

}

}

private void resetCell(Coordinates coordinates) {

Cell cell = grid.get(coordinates);

cell.aliveProperty().setValue(false);

}

Did you find it? How about now:

public void resetCells() {

for (int row = 0; row < grid.getRows(); row++) {

for (int column = 0; column < grid.getRows(); column++) {

resetCell(new Coordinates(row, column));

}

}

}

That second call to grid.getRows() should be grid.getColumns() (but you knew that, right?). How much simpler was it

to find the bug the second time around? Wouldn’t it have been better if the resetting functionality was added on a

different PR?

Admittedly, our unit tests should catch this. But what if the test data only uses square grids? Or even worse, what if this code isn’t even covered by our tests?

Bugs like this can go unnoticed as we focus on seemingly more complicated code when reviewing PRs. It’s surprising how often bugs creep into what should be trivial code. And this was in just 40(ish) lines. What happens when we get into the world of reviewing complex classes that are 400 lines long? Or multiple complex classes that are 400 lines long? It’s easy to see how identifying issues in a mammoth PR can be like trying to find hay in a needlestack.

Small PRs make it easier for you as an author and as a reviewer to spot problems.

Not blocking other updates

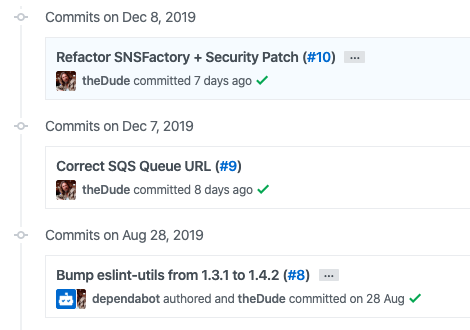

Let’s consider the following commit history:

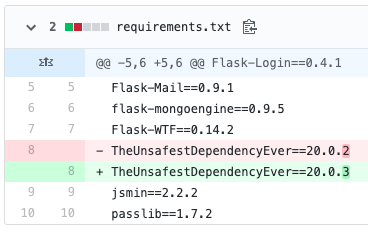

More specifically, let’s focus on the commit: Refactor SNSFactory + Security Patch. It’s clear that this commit did

more than one thing. Digging a little deeper, we can see that the security patch just consisted of a dependency version

bump:

Could this have been done on a separate PR? Absolutely! Should this have been done on a separate PR? Absolutely!

Why? Say, for example, refactoring the SNSFactory introduced an issue meaning that we sent an excessive amount of

messages to an SNS topic. We’d have to rollback our application to a previous version

and revert our security fix 😱. Not ideal.

Small PRs allow distinct updates to be deployed without being blocked by unrelated changes.

How?

Instead of going into the minutiae of how to make your PRs smaller, I’ve boiled it down to a couple of questions you should ask yourself before submitting a new PR.

Firstly:

“Does this PR do one thing?”

If the answer is “No”, then consider splitting it into smaller PRs.

Try to identify changes that logically fit together. Does the PR description encapsulate all of the changes that you have made? Are those dependency upgrades really necessary for this piece of functionality? Does this new feature need to be implemented on a single PR or could it be split up into smaller units?

Be pragmatic. You don’t have to create a separate PR for each function.

And, secondly:

“If I were asked to review this PR, would I be happy about it?”

If the answer is “No”, then consider splitting it into smaller PRs.

Try to view your PR with fresh eyes. If you read it from top to bottom, is it hard to follow? Are those extraneous updates distracting? Do they draw attention away from the main problem that you are attempting to solve?

Somebody has to take time out of their day to review your code. Put yourself in their shoes. Make it easy for them and they’ll, hopefully, return the favour with the PRs they send your way.

Final thoughts

Give it a try for a week. Make a conscious effort to keep your PRs small and gauge:

- the speed at which you are merging your PRs into master.

- how reactive people are to reviewing your PRs.

- the number of comments offering constructive criticism.

- how often you’re having to go back and fix bugs introduced by prior PRs.

I’m confident that you’ll see an improvement. At the very least, your number of contributions will start to look pretty healthy.

So one last time: keep those PRs small!

Thanks for reading.